Many architects are attracted by the profession’s aesthetic possibilities rather than by its moral component, and yet the basic mandate to provide structures for humanity encompasses both. All have to consider their level of involvement in creating punitive housing.

Sperry is asking questions about fundamental prison design. When he spoke at a panel discussion on prison design at the AIA Convention in Los Angeles in 2006, the AIA censored his images of Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo Bay. Of course this only helped him and his cause.Sperry is an architect with a broad vision about violence and militarism, but also a clear strategy about what to do in the here and now. He spoke with a calm zeal when we sat down for lunch at Delancey Street to talk about his recent activities.

Q: Where does your activism around prisons come from?

Raphael Sperry: The prison campaign came out of the other antiwar activism I was involved in during the run-up to the war in Iraq. I took part in the street demonstrations, playing with friends in a marching band, which was, for me, a good way to be on the street and visible and audible and feel like I had a particular role to play.

Raphael Sperry: The prison campaign came out of the other antiwar activism I was involved in during the run-up to the war in Iraq. I took part in the street demonstrations, playing with friends in a marching band, which was, for me, a good way to be on the street and visible and audible and feel like I had a particular role to play.

Despite the largest demonstrations that the world had ever seen, we didn't succeed in convincing a majority of the American voting public that the war was wrong. I felt that more work was necessary to shift public attitudes so that the next war, or the next violent solution to a different kind of problem, would not be so appealing again.

Q: Let’s talk about the relationship between the war and prisons.

Sperry: Despite the frequent evocations that America's a peace-loving country, we're actually a pretty militaristic country. Our military is the largest in the world, and it's engaged all over the place. We spend as much on weapons as the rest of the world combined. In some ways, Vietnam was the template for the current generation of American warfare. In the debate over the Iraq war, instead of feeling like Vietnam was a lesson that war is not a good way to solve problems, and that should it be avoided, many Americans thought the lesson was that we needed a new war that we could “win” in order to show that America is still number one.

There are a lot of Americans who are willing to tolerate war. The military -industrial complex clearly controls its slice of the budget, and nobody fights with it.

Q: But there is a difference between the Democrats and the Republicans on this?

Sperry: With the Republicans, it seems like that's part of their ideology. Whereas the Democrats, who may be ideologically opposed to it, feel like they have to jettison that to gain popular support.

To paraphrase Bill Clinton, when people are scared, they'd rather vote for somebody who's strong and wrong than somebody who's weak and right. I was tired of having government that was willfully wrong on the issues of war and peace kill other people in my name with my money. I wanted to try to do something, to the degree that I could, try to change this underlying acceptance of war and violence as a way to solve problems. Going out on street corners, handing out leaflets against the war, was not getting anybody to change their minds.

Sperry banging the drum against the war

Q: At least you had fun playing music.

Sperry: I did, I had a lot of fun. It was also my first experience with the jail system.

Q: Because you got arrested?

Sperry: Yes, I got arrested.

Around the same time, I was invited to join the board of ADPSR, which of course has a long track record of being a peace organization around antinuclear issues. I wanted to try to do some outreach to architects.

Q: Why architects?

Sperry: There’s no way that I could influence the opinion of 300 million people, but maybe I could influence fellow architects. If you want people to rethink their acceptance of violence in international policy and warfare, it helps to have something in common with the person you want to talk to. Rather than handing them a handbill on a street corner, you can have a conversation at an AIA meeting or a convention, or through the professional media. It’s a way to establish common ground so people will listen to you. Our culture is so media-saturated that it's important to protect yourself from listening to too many messages, because otherwise none of us could be productive at anything.

Q: We're getting less productive.

Sperry: Yes, it's true. But it seemed like this was an important conversation for people to have. And at the same time, through the group of musicians I was playing with who were radical community organizers of different types, I had heard about the critique of the prison system as the prison -industrial complex. That stuck in my mind, because I want to talk to architects on the one hand, and the prison system is a network of buildings.

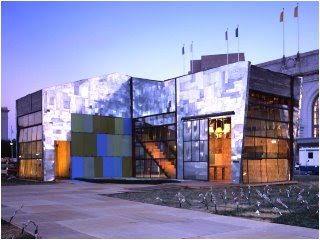

Photos of the Delano II prison in California, courtesy of Calif Dept of Corrections and Rehabilitation

Q: Tell me more about this critique.

Sperry: There are a lot of social issues that have been taken in the wrong direction because of the American military – because of how expensive it is, and also because of how it makes our society more violence-prone. Arguably, that's why we don't have a good healthcare system, arguably it's why other social issues in the United States – like social security, income security for elderly people, education, working conditions, and so forth – are so degraded compared to those in other wealthy countries. Unlike prison, with a lot of those issues, it is harder to say, “it's just about the buildings,” and with my intended audience of architects I wanted to talk about buildings, because we’re responsible for the built environment of our society. The idea of a “prison -industrial complex” is like the military one in that it’s an interconnected series of public and private institutions that use public money but function with little to no real public oversight because of the imagined threat to security that would result if their business dealings were made public.

Q: What is the connection of the military -industrial complex and the prison -industrial complex?

Sperry: Both of them rely on a simplistic division of the world into good people and bad people, good guys and bad guys, and they rely on a very clear rule that it's okay to use unrestrained violence against the bad guys. As soon as you know who the bad guys are, in the case of Iraq, you go out there and kick the shit out of their country. It doesn't matter how many innocent people die, because American violence is on the right side, against the bad guys. And since we're the good guys, whatever we do is okay. And not only that, it's important to punish the bad guys. That was the way that people understood the Iraq war. That's why capturing Saddam Hussein and executing him was such a big deal. If you really thought bringing democracy and liberation to 25 million people was important, the fate of one man couldn't possibly really be that important. But if it's a moral story about watching the bad guys be punished by the good guys and get their comeuppance so the good guys win in the end, then it kind of made sense to invade that whole country.

Pelican Bay State Prison

Q: And prisons are the domestic counterpart to this narrative?

Sperry: Yes. The domestic narrative is that the country's full of bad guys who are criminals, and if we put them behind bars, then the good guys would be safe. And it's okay to use violence against the bad guys. The American prison system, it turns out, has been widely criticized around the world by human rights advocates for the way it operates. Sometimes those are issues of a few bad apples, like the stories about Corcoran State Prison in California, where prison guards arranged gladiator-style fights between prisoners and shot at people with impunity. But it's much worse than that – we have systematic problems that make our whole approach to incarceration (and to criminal justice more generally) unethical in major ways. For example, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have pointed out that long-term solitary isolation is by its very nature a violation of human rights, as defined by most developed countries. Yet the United States has very clear policies in most of the states and the federal system allowing the use of long-term solitary isolation. They have entire buildings and entire wings of many buildings dedicated to isolation, so they're ready, willing, and able to perpetrate human rights abuses as a matter of policy.

I think a lot of people have the idea that once somebody's a convicted criminal, whatever you do to them is okay. Because they're bad guys, the important thing is to punish them.

I wanted to reinforce what I think is a better, more adult, mature, peaceful, and progressive way of responding to crime. There are a lot of promising alternatives to incarceration that actually work and that focus on healing the injuries caused by crimes, restoring damaged communities, and dealing with the roots of crime, whereas our current system has tried to do those things for over thirty years and hasn’t produced any benefits for public safety. Its very size – over 2.3 million people – makes it the largest prison system in the world (and the largest per capita), and involves over 5,000 buildings, most of them built in the last thirty years. And for what? Our crime rates are no better than they were thirty years ago, and the communities where most perpetrators come from (and where most crimes occur) are still doing as poorly as they were before. People of all types are still afraid of crime – having more prisons almost seems to make the problems around crime bigger. It’s not like some day we will lock up the last bad guy out there and then everyone will be safe – it doesn’t work like that.

I think that people who embrace the international version of “bad guys need to get punished with violence” are going to embrace the domestic version. If we work on the prison issue and get people to change their minds about what it means to be a good guy or a bad guy, and understand that the world is more complicated, that violence doesn’t have to be used to respond to these social problems, then eventually this kind of thinking could also play out in the international arena. If violence is no longer our first recourse against criminals at home, then I think we will also be much less likely to use war against opposing nations abroad.

Future blog entries will include Sperry’s strategies and experiences trying to influence his fellow architects.