|

| Julius Shulman Los Angeles: The Birth of a Modern Metropolis |

When Sam Lubell, the West Coast editor of the Architect’s Newspaper, told me that he was working on a new book on Julius Shulman, I thought he was crazy. We already had several titles, and is there a lot more to say? He began mining the archive at the Getty Research Institute for a different narrative, and indeed, the story turns out to be much larger than we imagined. In this interview, Sam tells us his thinking behind the new volume, entitled Julius Shulman Los Angeles: The Birth of a Modern Metropolis.

I enjoyed the essays that begin each chapter, but there is not a lot of text in this book. What was your role?

I did write a fairly lengthy introduction providing background about Julius’s work in Los Angeles, his photographic approach, his love of storytelling and of Los Angeles, and his concurrent blossoming with the city. Julius’s daughter, Judy McKee, also wrote a foreword that’s a more personal reflection on her father’s career and his relationship with Los Angeles. The bulk of the work, though, was curating Julius’s photographs. There are well over 100,000 photos in the Getty archive, and we had to somehow narrow it down to about 220. That took over a year and a half of visiting the Getty Research Institute and bringing the pictures into a coherent and fresh body of work.

How did the project evolve?

Rizzoli originally wanted to do a book on Julius’s interiors. But we realized early on that we wanted to differentiate it from the many other Shulman books out there. Anne Blecksmith at the Getty Research Institute pointed us in the direction of his lesser-known photos, which in the archive are the higher numbered boxes of contact sheets. When we started looking through those, we knew we had uncovered another side of Julius’s work that we thought needed to be shared. Most of this work was in the Los Angeles region, so we decided to focus on that. And we were most intrigued by the work from the 1940s to the 1960s—sort of the glory days of Los Angeles and of Julius. So that’s how we started to narrow it down.

You met him fairly late in his life. What were your impressions of him?

Even with diminished faculties, he had an amazing charisma and presence. Just his smile and his direct manner of speaking kept you in a sort of spell. Not many people have that effect. And he always made you feel welcome. He would welcome anyone who loved architecture into his home and made them feel like part of his life. You could tell how much he loved what he did and where he lived. And he never hesitated to show off his work. When you look at all of these factors, and the sort of legend he built up for himself, it’s not surprising that he was as successful as he was.

As you point out, Shulman had an eye for composition but also an ability to spin a tale. Do you have a favorite tale?

It’s really difficult to narrow it down, because there are so many. I loved talking to him about the picture he took of Neutra’s Miller House in Palm Springs. The shot shows Mrs. Miller sitting in front of a large window that shows off the expanse of the desert. He was telling a story not just about the beautiful architecture, or about Mrs. Miller (who he pointed out had “nice legs”), but also about the majestic expanse of nothingness that both were now part of. That’s what made the picture stand out, and what grabbed people. It’s funny because now that house is completely surrounded by development, and that magic effect is gone. Sort of like much of the region.

What were some of Shulman’s biases?

Julius had an eye for visual drama. With modernist buildings, he loved capturing the strong lines stretching toward the horizon, the merging of inside and outside, and the often heroic exposed structures. Some of his earlier shots, in more enclosed, traditional buildings, lack this sense of visual drama. In my opinion, he was of course an amazing photographer, but he also found a style of architecture that really matched his sense of optimism and excitement, and it showed in his pictures. His less “architectural” pictures were able to hook you in the same way. He again used strong lines and diagonals that could “suck you in.” He often framed pictures like a filmmaker. And he knew what it was about each shot that would make you stop in your tracks.

One visual bias I have noticed is that Shulman favored the horizontal image. I suppose that is a chicken/egg kind of question. Los Angeles was a horizontal city. Do you agree?

Yes, I think that’s correct. My instinct is that it’s a function of what he shot. The majority of the houses and landscapes he visited were horizontal—a jarring contrast with the verticality of traditional cities like New York and Chicago. He was capturing that sense of expanse and sprawl. When he did shoot in vertical cities, you’ll notice that most of his shots were vertical. So I think he was just taking in what he saw and maximizing its effect.

You write that most of Shulman’s archive is not architectural. Are you trying to reposition him as a recorder of culture as much as modern architecture?

It’s certainly not one or the other. He recorded architecture as well as culture and development together. Of course most of his assignments were to shoot buildings. But they were not all precious and “architectural.” Most of his work was the bread and butter variety that really filled up the city. And it’s looking at those works in their urban and suburban contexts that gives us a much fuller perception of the city.

|

| © J. Paul Getty Trust, Julius Shulman Los Angeles: The Birth of a Modern Metropolis by Sam Lubell and Douglas Woods, Rizzoli New York, 2011. Mobil Gas Station, Smith and Williams, Anaheim, 1956. |

Why did you select the very architectural image of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Freeman House living room for the cover if you were trying to get away from the architectural?

We start with what people expect from Julius: a beautiful piece of architecture. But then as you look at it, you become sucked into the scene of the city outside straight ahead of you. You see the streetscapes of Hollywood and you want to venture outside to see what it’s all about. It’s an arresting picture (always important for selling books!) that also tells the story of the book. His work was about architecture but also about the city around the architecture.

Is this book going to open up a new interpretation of Shulman?

I don’t think it will transform people’s impression of Shulman, but it will certainly give people a more complete idea of his legacy. Of course he still took shots of the most famous modernist buildings in the world. But he also took shots of every other piece of architecture imaginable.

Did he throw out much work? By that, I mean did he edit his archive before he filed the image?

That’s an excellent question. It’s unclear how much of his archive was self edited. Even the curators at the Getty don’t know the real answer to that. But given how many pictures are in the archive, and the variety of images in each shoot, I would have to guess that he kept most of the stuff that he shot. He certainly wasn’t afraid to put in duplicate images or images with crop marks or other edits on them. Some even have doodles on them, such as an image of Greta Grossman with glasses and a moustache drawn onto her. I have no idea what that was about. I wish I could ask him more about it.

When his house by Soriano was new, he had a view out over the canyons and the city. Over time the garden became quite overgrown, like a jungle. Was it his fortress against the city that was choking on its rapid growth?

That’s another question that I’d love to ask Julius. I know that the thing he loved most about Los Angeles was its combination of urbanity and nature. The fact that his garden became overgrown I would imagine had more to do with his single-minded focus on his photography. But he loved the respite that the house provided him. From what I could tell, it was his favorite place in the world.

|

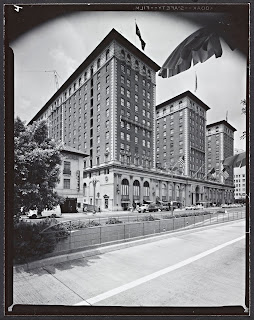

| © J. Paul Getty Trust, Julius Shulman Los Angeles: The Birth of a Modern Metropolis by Sam Lubell and Douglas Woods, Rizzoli New York, 2011. Julius Shulman’s home designed by Raphael Soriano, 1951. |

When you were preparing this book, what surprised you the most?

I was surprised by the sheer magnitude of Shulman’s work. His log book is amazing. He shot something basically every day of his life. And when he wasn’t working, he was shooting things on vacation.

What’s your next project?

Ha! It’s a good project. Nothing is official, so I hesitate to share. But I’m working on an exhibit and book about projects that never came to fruition in Los Angeles called Never Built: LA. I’m also talking about a book about one of Shulman’s contemporaries, Marvin Rand. We’ll see where those go!

|

| Julius Shulman, courtesy LA Times |